Obesity: How a single molecule may disrupt the body’s metabolism

Previous research shows obesity can negatively impact a number of the body’s systems and increase a person’s risk for several diseases.

A new study found evidence that shows how obesity affects the body on a metabolic level by disrupting mitochondrial function.

The results could potentially pave the way for new obesity treatments and prevention strategies.

Approximately 38% of the world’s population is considered obese or overweight, according to the World Obesity Federation.

Researchers estimate the majority of the global adult population will be either overweight or obese by 2030.

Previous research shows obesity can negatively impact a number of the body’s systems, including the,,, andsystems. It can also raise a person’s risk for several diseases including:

certain types of

Now researchers from the University of California — San Diego report evidence that obesity also affects the body on a metabolic level. Scientists believe this finding may lead to the development of new therapies for the treatment or prevention of obesity.

The study was recently published in the journal.

Metabolic changes caused by obesity

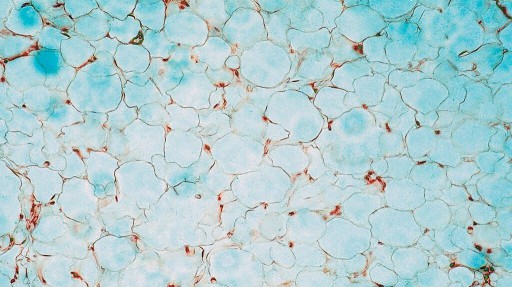

Obesity is defined as accumulating too much body fat within theof the body.

Previous studies show that obesity causes metabolic changes within the white adipose tissue causing:

(cell death)

Lead study author Dr. Alan Saltiel, professor in the Department of Medicine at the University of California — San Diego School of Medicine, told Medical News Today his lab has been working for 40 years to understand hormones like insulin control and where and when energy is stored or used.

“Obesity has a major impact on how well these hormones do their job, and vice versa,” Dr. Saltiel said.

“In the last few years, we’ve turned our attention to the ways that fat and liver cells adapt to conditions associated with overeating when the cells are flooded with nutrients. The interesting thing is that these cells become more efficient at storing energy and less efficient at burning it, which is one reason why it is so hard to lose weight,” he continued. “We’ve been exploring the underlying molecular changes that explain this.”

— Dr. Alan Saltiel, lead study author

Mitochondrial dysfunction in obesity

Dr. Saltiel explained that obesity causes metabolic abnormalities in the body because the body has to manage excessive amounts of energy due to the condition.

In other words, the body has to find a way to store energy or excess calories since there is a limit on how much can be burned off.

“Thus, adjustments are made, and this change in mitochondrial structure and function is one that we highlight in this paper,” he added.

Using a mouse model, Dr. Saltiel and his team found when mice were fed a high fat diet, the mitochondria — known as the “powerhouse of the cell” — within fat cells fragmented into smaller mitochondria. Researchers found these smaller mitochondria could not burn as much fat as when the larger mitochondria were all together.

“In the normal, non-obese state, mitochondria maintain their health through a cycle of continual fusion and fission, which means they break apart and reform,” Dr. Saltiel explained. “We found that the changes that occur in obesity tip the scales so that mitochondria break apart more — the process known as fission.”

The researchers also discovered that these changes only occur in one type of fat cells — the kind found below the skin (subcutaneous) that is mainly in the hips and thighs.

“This is thought to be the good adipose depot, as it has the potential to burn as well as store fat,” Dr. Saltiel said.

“We found that mitochondria are normally longer and more active in this fat depot compared to the adipose tissue found in the midsection — called visceral fat — but obesity causes excessive mitochondrial fission in subcutaneous fat, so it looks more like visceral fat and loses its ability to burn fat,” he noted.

Turning off the metabolism-disrupting molecule

During their research, Dr. Saltiel and his team discovered this fragmentation of mitochondria was caused by a single molecule called.

“We’ve been studying the role of RalA in the actions of insulin for a long time,” Dr. Saltiel said.

“We were surprised to discover that RalA is a master regulator of mitochondrial fission, and when it is chronically activated in obesity, it tips the scales toward fission.”

When scientists deleted the gene associated with the RaIA molecule in mice, they were able to protect them from weight gain from a high-fat diet.

Researchers believe this finding could potentially lead to new ways of preventing and/or treating obesity.

“I think the primary finding here is that there is mitochondrial dysfunction produced by obesity through this RalA-dependent pathway,” Dr. Saltiel explained.

“It is possible that there are new drug targets in the pathway that may allow us to reverse the excessive mitochondrial fission and thus increase fat burning. But this is a long way off, and who knows what other important processes are controlled by this pathway in the body,” he added.

Thinking about weight loss on a cellular level

MNT also spoke with Dr. Mir Ali, bariatric surgeon and medical director of MemorialCare Surgical Weight Loss Center at Orange Coast Medical Center in Fountain Valley, CA, about this study.

Dr. Ali said he thought the research was very interesting as it showed how obesity is adversely affecting the body even at a cellular level.

“I think most people understand that obesity is detrimental to their health, but to see this go down to the cellular level makes it even more impactful, I think,” he continued. “I think that if more people understand how widely impactful obesity is on the body, it will motivate some people to do something about it.”

Dr. Ali said the study findings that show how obesity affects the mitochondria could lead to the development of medication that could block that effect and have a role in fighting obesity.

“This is very early research — it’s going to require a lot more work finding something that can block these kinds of effects on the cellular level,” Dr. Ali added. “It’s going to take a lot of work, but it’s encouraging that there’s something we can do at that level.”